Although the myths were often irrational, they nevertheless had been widely accepted as the “revelation of the gods.” The pervasiveness of the

muthos in the Greco-Roman world of the New Testament can be seen sticking up out of the New Testament like the tip of an iceberg above the water, and archaeology confirms the widespread presence of the gods in the everyday life of the Greek and Roman people of New Testament times. The average Greek or Roman was as familiar with the teachings about the adventures of the gods as the average school child in the United States is familiar with Goldilocks and the Three Bears or Snoopy and Charlie Brown. Thus, when Paul and Barnabas healed a cripple in Lystra, the people assumed that the gods had come down in human form (

Acts 14:11), and no doubt they based their assumption on the legend that Zeus and Hermes had once come to that area in human form. While Paul was in Athens, he became disturbed because of the large number of idols there that were statues to the various gods (

Acts 17:16). In Ephesus, Paul’s teaching actually started a riot. When some of the locals realized that if his doctrine spread, “the temple of the great goddess Artemis will be discredited, and the goddess herself, who is worshiped throughout the province of Asia and the world, will be robbed of her divine majesty” (

Acts 19:27). There are many other examples that show that there was a

muthos, i.e., a body of religious knowledge that was in large part incomprehensible to the human mind, firmly established in the minds of some of the common people in New Testament times.

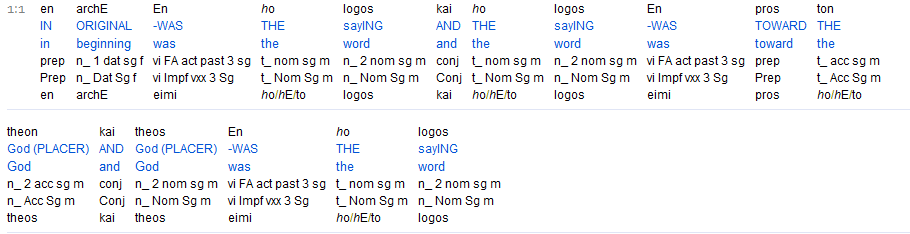

Starting several centuries before Christ, certain Greek philosophers worked to replace the

muthos with what they called the

logos, a reasonable and rational explanation of reality. It is appropriate that, in the writing of the New Testament, God used the word

logos, not

muthos, to describe His wisdom, reason, and plan. God has not come to us in mystical experiences and irrational beliefs that cannot be understood; rather, He reveals Himself in ways that can be rationally understood and persuasively argued.

In addition to the cultural context that accepted the myths, at the time the Gospel of John was written, a belief system called Gnosticism was taking root in Christianity. Gnosticism had many ideas and words that are strange and confusing to us today, so, at the risk of oversimplifying, we will describe a few basic tenets of Gnosticism as simply as we can.

Gnosticism took many forms, but generally, Gnostics taught that there was a supreme and unknowable Being, which they designated as the “Monad.” The Monad produced various gods, who in turn produced other gods (these gods were called by different names, in part because of their power or position). One of these gods, called the “Demiurge” created the earth and then ruled over it as an angry, evil, and jealous god. This evil god, Gnostics believed, was the god of the Old Testament, called

Elohim. The Monad sent another god, “Christ” to bring special

gnosis (knowledge) to mankind and free them from the influence of the evil

Elohim. Thus, a Gnostic Christian would agree that

Elohim created the heavens and the earth, but he would not agree that He was the supreme God. Most Gnostics would also state that

Elohim and Christ were at cross-purposes with each other. This is why it was so important for

John 1:1 to say that the

logos was

with God, which at first glance seems to be a totally unnecessary statement.

The opening of the Gospel of John is a wonderful expression of God’s love. God “wants all men to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth” (

1 Tim. 2:4). He authored the opening of John in such a way that it reveals the truth about Him and His plan for all of mankind and, at the same time, refutes Gnostic teaching. It says that from the beginning there was the

logos (the reason, plan, power), which was with God. There was not another “god” existing with God, especially not a god opposed to God. Furthermore, God’s plan was like God; it was divine. God’s plan became flesh when God impregnated Mary.

“and the word was with God.” This is strange language to us, so it is important to know that it was not strange to the Jews. While we would say a person “has wisdom” or “is wise” it was a common way of speaking among the Jewish people to say a word, or knowledge, or wisdom, was “with” a person. For example, the Hebrew text of

Proverbs 2:1 speaks of the commandments being “with” a person, and so does

Proverbs 7:1.

Proverbs 11:2 speaks of wisdom being “with” the humble, not just the humble “having wisdom” or “being wise” and

Proverbs 13:10 says wisdom is “with” people who take advice.

Job spoke to God about His actions, and spoke of what God hid in His heart, and then Job said, “I know that this [God’s secret plans and purposes] is with you” (

Job 10:13; the Hebrew text says “with you” although it's not translated that way in many English versions). We would say “I know you have these things” but the Hebrews said “I know these things are with you.” Job also spoke of what God desired, and concluded that “many such things [that God desires and that are appointed] are with him” (

Job 23:14).

Job 27:11 also speaks of things being “with” God.

When God gave the Ten Commandments, Moses said that God had come to test the people and also so that the fear of God would be “with them” (as per the Hebrew text). We today would never say “so that the fear of God will be with you” as if the fear of God was another entity somehow together with the people, we today would simply say “so that you will fear God.” The Jews used the same “with” language in the Bible and in other writings as well.

Once we understand the

logos in

John 1:1 to be God’s purpose and plan, we can see that if

John 1:1 was written in today’s English, we would likely say something like “In the beginning was the plan, and God had that plan, and what God was the plan was.” We would not say that the plan was “with God.” But the ancient Jews had said knowledge and wisdom were “with” people for millennia, and for them to speak that way was perfectly natural. However, if we today are going to understand the prologue of John (

John 1:1-18), it is imperative that we understand that

logos is a masculine noun and it is personified in the Prologue. Wisdom and the

logos were personified in the literature of the Jews from long before the time that John wrote, and that influenced how he wrote the prologue of John. Personification was widely used in Jewish literature. For example, Proverbs portrays Wisdom as a woman helping God with His creation of the world (

Prov. 8:22-31).

John 1:1 is not portraying a preincarnate Christ being with God. That would have been a nonsensical concept to the ancient unbelieving Jews and Greeks—remember, John was writing to get people to believe (

John 20:30-31)—it was portraying that God used wisdom and a plan in restoring mankind to Himself, and that logos was a “plan” made perfect sense to those ancient unbelievers.

“and what God was, the word was.” This phrase is stating that the Word has the attributes of God, such as being true, trustworthy, etc. It makes perfect sense that if the Word is the expression of God, then it has attributes of God. Although almost every English Bible translates the last phrase of

John 1:1 as “and the Word was God.” and it should not be translated that way. To understand that, we first should be aware of how the Greek text of the New Testament was written and how the Greeks used the word

theos “God” or “god.”

Although we make a distinction between “God” with a capital “G” and “god” with a lowercase “g” the original text could not do that. The original text of both the Old and the New Testament was written in all capital letters, so in Greek, both “God” and “god” were “GOD” (ΘΕΟΣ; THEOS). This meant the person reading the Scripture had to pay close attention to the context. When our modern English versions mention “the god of this age” (

2 Cor. 4:4), one way we know that the word “god” refers to Satan is because it is spelled with a lowercase “g.” But if our versions read in all capitals like the ancient Greek text and said, “THE GOD OF THIS AGE” then how would we know who this “GOD” was? We would have to discover who he was from the context. The people reading the early Greek texts had to become very sensitive to the context to properly understand the Bible. An unintended consequence of modern capitalization, punctuation, and spacing in the text is that it has made the modern reader much less aware of and sensitive to the context.

What the word “GOD” referred to in any given context was further complicated by the fact that, as any good Greek lexicon will show, the Greek word

theos (

#2316 θεός) was used to refer to both gods and goddesses, or was a general name for any deity, or was used of a representative of God, and was even used of people of high authority such as rulers or judges. The Greeks did not use the word “GOD” like we do, to refer to just one single Supreme Being with no other being sharing the name. The Greeks were polytheistic and had many gods with different positions and authority, and rulers and judges who represented the gods or who were themselves of high authority, and

theos was used of all of those. Some of the authorities in the Bible who are referred to as ΘΕΟΣ include the Devil (

2 Cor. 4:4), lesser gods (

1 Cor. 8:5), and men with great authority (

John 10:34-35;

Acts 12:22).

When we are trying to discover what GOD (ΘΕΟΣ; THEOS) is referring to in a verse, the context is always the final arbiter. However, we do get some help in that it is almost always the case in the New Testament that when “GOD” refers to the Father, the definite article appears in the Greek text (this article can be seen only in the Greek text, it is never translated into English). Translators are normally very sensitive to this. The difference between

theos with and without the article occurs in

John 1:1, which has two occurrences of

theos: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with the

theos, and the Word was

theos.” Since the definite article (“the”) is missing from the second occurrence of “

theos” (“God”) the most natural meaning of the word would be that it referred to the quality of God, i.e., “divine” “god-like” or “like God.” The

New English Bible gets the sense of this phrase by translating it “What God was, the Word was.” James Moffatt, who was a professor of Greek and New Testament Exegesis at Mansfield College in Oxford, England, and author of the well-known

Moffatt Bible, translated the phrase “the

logos was divine.”

As we said above, although the wording of the Greek text of

John 1:1 certainly favors the translation “and what God was, the Word was” over the translation “the Word was God” the context and scope of Scripture must be the final arbiter. In this case, we have help from the verse itself in the phrase “the Word was with God.” The Word (

logos) cannot both be “with” God and “be” God. That is nonsensical. It is similar to us being able to discern that Jesus Christ is not God from reading

2 Corinthians 4:4 and

Colossians 1:15, which say that Jesus is the image of God. One cannot be both the image of the object and the object itself. We Christians must become aware of the difference between a genuine mystery and a contradiction. In his book,

Against Calvinism, Roger Olson writes: “We must point out here the difference between mystery and contradiction; the former is something that cannot be fully explained to or comprehended by the human mind, whereas the latter is just nonsense—two concepts that cancel each other out and together make an absurdity.” The truth in the verse is actually simple: the

logos, the plan, purpose, and wisdom of God, was with God, and what God was (i.e., holy, true, pure, righteous, etc.) his

logos was too.