I have this work on electronic copy and can find no such reference. I did a search on the phrases "Paul views all people as condemned," and "but because they participate in it.” with no hits

I did find

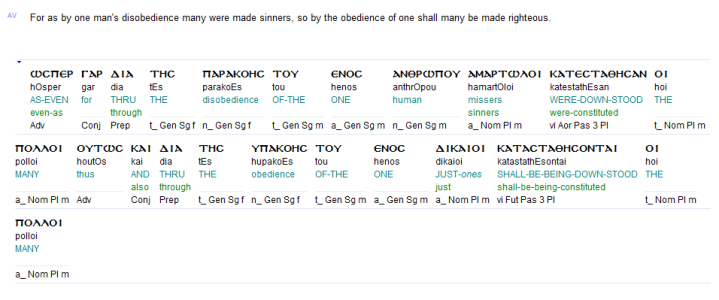

18 Paul now summarizes his basic argument in this paragraph, finally stating the full comparison between Adam and Christ that he began in v. 12, parenthetically remarked on in vv. 13–14, and elaborated on in vv. 15–17. After the negative comparisons of vv. 15, 16a, and 16b, and the qualitative contrasts (“how much more”) in vv. 15b and 17, Paul returns to the simple comparative structure of v. 12. This comparative structure is the basic building block of vv. 18–21, Paul using it three times to state the parallel between Adam and Christ: “as … so” (v. 18); “just as … so” (v. 19); “just as … so” (v. 21). Verse 20, like vv. 13–14, breaks into the sequence with a comment about the role of the Mosaic law in the general salvation-historical scheme of Adam and Christ.

Paul again expresses himself in v. 18 elliptically, leaving important elements to be supplied by the reader. Probably we should translate something like “as condemnation came to all people through the trespass of one man, so also did the righteousness that leads to life126 come to all people through the righteous act of one man.”128 Paul again asserts that Adam’s trespass has been instrumental in leading to the “condemnation” of all people.

In keeping with the alternatives we explored for the interpretation of v. 12d, some take this instrumental connection to be mediate—Adam’s “trespass”-human sinning-“condemnation” of all—and others immediate—Adam’s “trespass”-“condemnation” of all. While the text does not rule out the former, we think the latter, in light of the parallel with Christ and the lack of explicit mention of an intermediate stage, to be more likely (cf. the discussion on 5:12d).

In the last paragraph we have spoken of “justification leading to life” as applicable to believers. But does not Paul’s explicit statement that this justification leading to life is “for all people” call into question the propriety of so confining justification only to some people? Indeed, this verse simply makes explicit what seems to be the logic of the paragraph as a whole, as Paul has repeatedly used the same terminology of those who are affected by Christ’s act as he has of those who are affected by Adam’s. And if, as is clear, Adam’s act has brought condemnation to all, without exception, must we not conclude that Christ’s act has brought justification and life for all? A growing number of scholars argue that this is exactly what Paul intends to say here. Recently, for instance, A. Hultgren has urged that the universal statements in this passage must be taken seriously, as descriptive of a “justification of humanity” that will be revealed at the judgment. Some people are justified by faith in this life, but those who do not accept the offer of God in this life are nevertheless assured of being justified at the judgment.

Such universalistic thinking is, naturally, very appealing—who likes the idea that many people will be consigned to the eternal punishment of hell? But if, as seems clear, many texts plainly teach the reality of such punishment for those who do not embrace Christ by faith in this life (cf., e.g., 2 Thess. 1:8–9; Rom. 2:12; and the argument of 1:18–3:20), those who advocate such a viewpoint are guilty of picking and choosing their evidence. But can we reconcile the plain universalistic statements of this verse with these other texts that speak of the reality of hell? Some deny that we can, suggesting that we face a paradox on this point that God will resolve someday. Others argue that what is universal in v. 18b is not the actual justification accomplished in the lives of individuals, but the basis for this justification in the work of Christ. Christ has won for all “the sentence of justification” and this is now offered freely to all who will “receive the gift.” Nevertheless, whatever one’s view on “limited atonement” might be (and the view just outlined is obviously incompatible with this doctrine), it is questionable whether Paul’s language can be taken in this way. For one thing, Paul always uses “justification” language of the status actually conferred on the individual, never of the atonement won on the cross itself (cf. particularly the careful distinctions in Rom. 3:21–26). Second, it is doubtful whether Paul is describing simply an “offer” made to people through the work of Christ; certainly in the parallel in the first part of the verse, the condemnation actually embraces all people. But perhaps the biggest objection to this view is that it misses the point for which Paul is arguing in this passage. This point is that there can be an assurance of justification and life, on one side, that is just as strong and certain as the assurance of condemnation on the other. Paul wants to show, not how Christ has made available righteousness and life for all, but how Christ has secured the benefits of that righteousness for all who belong to him.

In this last phrase, we touch on what is the most likely explanation of Paul’s language in this verse. Throughout the passage, Paul’s concern to maintain parallelism between Adam and Christ has led him to choose terms that will clearly express this. In vv. 15 and 19, he uses “the many”; here he uses “all people.” But in each case, Paul’s point is not so much that the groups affected by Christ and Adam, respectively, are coextensive, but that Christ affects those who are his just as certainly as Adam does those who are his. When we ask who belongs to, or is “in,” Adam and Christ, respectively, Paul makes his answer clear: every person, without exception, is “in Adam” (cf. vv. 12d–14); but only those who “receive the gift” (v. 17; “those who believe,” according to Rom. 1:16–5:11) are “in Christ.” That “all” does not always mean “every single human being” is clear from many passages, it often being clearly limited in context (cf., e.g., Rom. 8:32; 12:17, 18; 14:2; 16:19), so this suggestion has no linguistic barrier. In the present verse, the scope of “all people” in the two parts of the verse is distinguished in the context, Paul making it clear, both by his silence and by the logic of vv. 12–14, that there is no limitation whatsoever on the number of those who are involved in Adam’s sin, while the deliberately worded v. 17, along with the persistent stress on faith as the means of achieving righteousness in 1:16–4:25, makes it equally clear that only certain people derive the benefits from Christ’s act of righteousness.

Douglas J. Moo, The Epistle to the Romans (The New International Commentary on the New Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1996), 340–344.

Where Moo acknowledges

12d, some take this instrumental connection to be

mediate—Adam’s “trespass”-human sinning-“condemnation” of all—and others immediate—Adam’s “trespass”-“condemnation” of all.

While the text does not rule out the former, we think the latter, in light of the parallel with Christ and the lack of explicit mention of an intermediate stage, to be more likely (cf. the discussion on 5:12d).

Mediate imputation being

The doctrine of mediate imputation states that the sin of Adam is not imputed directly to his posterity; instead, Adam’s corrupt and sinful nature is imputed directly, and Adam’s sin is imputed as a consequence of the imputation of Adam’s corrupt nature12

BTW I did find this

First, we could be content to posit an unresolved “tension” between the individual and the corporate emphasis.

Paul in v. 12 asserts that all people die because they sin on their own account; and in vv. 18–19 he claims that they die because of Adam’s sin. Paul does not resolve these two perspectives; and we do wrong to try to force a resolution that Paul himself never made. A systematic theologian may have to find a resolution; but we exegetes need not insist that Paul in this text assumes or teaches one. Now it is certainly the case that we can err by insisting that a text give us answers to all our questions about a topic or (still worse) by foisting on a biblical author theological categories that do not fit that author’s teaching. But we can also fail to do our job as exegetes by failing to pursue reasonable harmonizations that the author may assume or intend. So we think it is legitimate to ask whether Paul suggests any resolution of the tension between individual and Adamic responsibility for sin in this text.

Douglas J. Moo, The Epistle to the Romans (The New International Commentary on the New Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1996), 324–325.