Your emphasis is on the wrong word.

You make me smile-quite a feat.

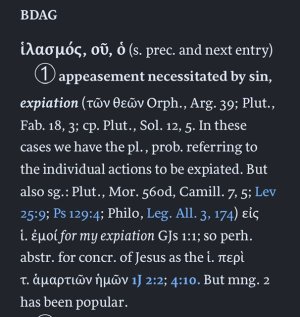

Even if we take hilastērion to carry here its LXX meaning as

opposed to its extra-biblical meaning, Paul is obviously using the

expression metaphorically –

Christ is not literally a piece of Temple

furniture!

Taken metaphorically rather than literally, however, the

expression could convey a rich variety of connotations associated

with sacrifice and atonement,

so that the sort of dichotomistic

reading forced by literal meanings becomes inappropriate.

Paul

was a Hellenistic Jew, whose writings bear the imprint of

Hellenistic Jewish thought (e.g., the natural theology of Rom 1 or

the Logos doctrine behind Rom 11.36), and he might have

expected his Roman readers to understand hilastērion in the customary sense. At the same time, by borrowing an image from

the Day of Atonement rituals, Paul also conveys to his hearers the

OT notion of expiation by blood sacrifice.

Thomas Heicke comments that already in the OT, “by means of abstraction, the ritual

itself turns into a metaphor,” thus building “the basis and starting

point for multiple transformations and further abstractions as well

as metaphorical charging in Judaism ... and Christianity (Rom

3:25: Christ as hilasterion – expiation or sacrifice of atonement,

etc.)” (Heicke 2016).

Christ’s death is thus both expiatory and propitiatory: “Since,

therefore, we are now justified by his blood, much more shall we be

saved by him from the wrath of God” (5.9).

Given the manifold

effects of Christ’s blood, hilastērion is doubtlessly multivalent in

Paul’s usage, comprising both expiation and propitiation, so that

a vague translation, for example, “an atoning sacrifice,” is about

the best one can give (cf. Heb 2.17; 1 Jn 2.2; 4.10).

---------------------------------------------------------------

biblethinker.org

Isaiah’s Servant of the Lord

Another significant NT motif concerning Christ’s death is Isaiah’s

Servant of the Lord. NT authors saw Jesus as the suffering Servant

described in Is 52.13–53.12.

Ten of the twelve verses of Isaiah 53 are

quoted in the NT, which also abounds in allusions and echoes of this

passage.

I have already mentioned the Synoptic Gospels’ accounts of

Jesus’s words at the Last Supper. In Acts 8.30–35, Philip, in response

to an Ethiopian official’s question concerning Isaiah 53 – “About

whom does the prophet speak?” – shares “the good news about

Jesus.” I Peter 2.22–25 is a reflection on Christ as the Servant of

Isaiah 53, who “bore our sins in his body on the tree.” Hebrews 9.28

alludes to Is 53.12 in describing Christ as “having been offered once

to bear the sins of many.”

The influence of Isaiah 53 is also evident in

Romans, I and II Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, I Timothy, and

Titus.

NT scholar William Farmer concludes, “This evidence indicates that there is an Isaianic soteriology deeply embedded in the

New Testament which finds its normative form and substance in

Isaiah 53” (Farmer 1998, p. 267; cf. Bailey 1998 and Watts 1998).

What is remarkable, even startling, about the Servant of Isaiah 53

is that he suffers

substitutionally for the sins of others.

Some

scholars have denied this, claiming that the Servant merely shares

in the punitive suffering of the Jewish exiles. But such an interpretation does not make as good sense of the shock expressed at

what Yahweh has done in afflicting His Servant (Is 52.14–53.1,10)

and is less plausible in light of the strong contrasts, reinforced by

the Hebrew pronouns, drawn between the Servant and the persons

speaking in the first-person plural:

Surely he has borne our griefs

and carried our sorrows;

yet we esteemed him stricken,

smitten by God, and afflicted.

But he was wounded for our transgressions,

he was bruised for our iniquities;

upon him was the chastisement that made us whole,

and with his stripes we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray;

we have turned every one to his own way;

and the LORD has laid on him

the iniquity of us all.

(Is 53.4–6)7

7 See Hermisson (2004) and Hofius (2004), who says that substitutionary punishment “is expressed several times in the passage and should undoubtedly be

seen as its dominant and central theme” (Hofius 2004, p. 164).

The Atonement 17

We may compare the LORD’s symbolically laying the punishment of

Israel and Judah upon the prophet Ezekiel, so that he could be said

to “bear their punishment” (Ezek 4.4–6).

Here, in Isaiah 53, the

Servant’s bearing the punishment for Israel’s sins is, however, not

symbolic but real.

The idea of substitutionary suffering is, as we have seen,

already implicit in the animal sacrifices prescribed in Leviticus.

Death is the consequence of sin, and the animal dies in the place

of the sinner.

By the hand-laying ritual that precedes the sacrifice,

the worshipper symbolically indicates his identification with the

animal that he will sacrifice. This identification should not be

thought of in terms of a magical penetration of the worshipper’s

soul into the animal, but in substitutionary terms. The animal’s

death is symbolic of the sinner’s death.

Thus, the animal “shall be

accepted for him to make atonement for him” (Lev 1.4). Similarly,

in Isaiah 53 the Servant is said “to make himself an offering for

sin” (v 10).

It is sometimes said that the idea of offering a human substitute

is utterly foreign to Judaism; but this is, in fact, not true. The idea of

substitutionary punishment is clearly expressed in Moses’s offer to

the LORD to be killed in place of the people, who had apostatized, in

order to “make atonement” for their sin (Exod 32.30–34). Although

Yahweh rejects Moses’s offer of a substitutionary atonement, saying that “when the day comes for punishment, I will punish them

for their sin” (v 34), the offer is nonetheless clear, and Yahweh

simply declines the offer but does not dismiss it as absurd or

impossible. Similarly, while Yahweh consistently rejects human

sacrifice, in contrast to the practice of pagan nations, the story of

God’s commanding Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac (whom the

NT treats as a type of Christ) shows that such a thing is not

impossible (Gen 22.1–19). In Isaiah 53, moreover, the idea of the

Servant’s substitutionary suffering is treated as extraordinary and

surprising. The LORD has inflicted on His righteous Servant what He

refused to inflict on Isaac and Moses.

The suffering of the Servant is agreed on all hands to be punitive.

In the OT, the expression “to bear sin,” when used of people,

Jul 2018 at 16:28:40,

subject to the Cambridge Core terms

typically means to be held culpable or to endure punishment (e.g.,

Lev 5.1; 7.18; 19.8; 24.15; Num 5.31; 9.13; 14.34).

The Servant does

not bear his own sins, but the sins of others (vv 4, 11–12).

Intriguingly, the phrase can be used regarding the priests’ action

of making atonement (e.g., Lev 10.17: “that you may bear the

iniquity of the congregation, to make atonement for them before

the LORD”). But the priests, unlike the Servant, do not suffer in so

doing. The punitive nature of the Servant’s suffering is clearly

expressed in phrases like “wounded for our transgressions,”

“bruised for our iniquities,” “upon him was the chastisement that

made us whole,” “the LORD has laid on him the iniquity of us all,”

and “stricken for the transgression of my people” (vv 5, 6, 8).