civic

Active Member

From the intro: Lamb of the Free- recovering the varied sacrificial understanding of Jesus death

This could very well be the best and most influential book written on Jesus death and its biblical meaning.

Andrew will summarize the key discoveries of this trajectory concerning the logic of OT sacrifice in what follows—and they are fascinating—so I do not need to do so here. The key point for us to grasp in this preliminary discussion is that this careful, historical work by Milgrom, along with those who argue like him, exposes the fact that the set of equations at the heart of the PSA model is, quite simply, untrue. The practice and logic of OT sacrifice has nothing to do with substitution, retribution, or punishment (i.e., negative retribution). Neither is it supplying a universal account of justice. The mechanism, logic, and concerns of OT sacrifice are completely different. As Andrew goes on to show, a number of significant reinterpretative tasks are set in motion by this realization, although I will mention just the key moves here since it will be better just to read what he says: 1.Where sacrifice is used in the NT, we now need to reorient our interpretations. What is going on in these texts is not PSA. A different logic is in play. Needless to say, the meaning of a lot of key texts utilizing sacrificial imagery shifts subtly but significantly—for example, the meaning of Romans 3:25. Andrew traces the most important such shifts in what follows. 2.Sacrifice disappears from many texts and arguments where previously we thought it was present. Simply because a passage discusses “atonement,” or even “salvation,” we no longer need to assume that the underlying logic and metaphorical register is actually “sacrifice.”

Many NT texts are consequently set free to make their own, more individuated contributions to our understanding of God’s saving activity through Christ. They can find different metaphorical fields and intertexts to be illuminated by. The discussion of soteriology, as Andrew shows, is diversified, complexified, and thereby enriched. 3.Financial metaphors and analogies are also caught up in this reevaluation. Simply because a text analogizes God’s work in Christ in terms of money no longer entails that God is enacting an event constrained by the parameters of negative retribution. God is not always exacting the payment of a debt from sinners meted out with pain. Something very different might be going on. Money and the financial system are, after all, very complicated metaphorical fields. They can speak much more clearly now of God’s gracious benefaction.6 The final critical result of all this reevaluation is, of course, that the account of the atonement in terms of PSA is damaged beyond all hope of redemption.

Its account of sacrifice is incorrect; its reach, presupposing sacrifice, is false; and its account of financial metaphors is false as well. At bottom, it has lost its biblical base almost entirely. (Andrew does not address appeals by PSA to non-sacrificial registers, but these will be limited and desperate.) It remains only then to press this good news through for all the rest of our thinking. We must press, that is, more deeply into a God of love, not retribution; into a God who eschews violence, rather than practicing it proportionately; and into a gospel rooted in divine benevolence and covenant, not in retribution and contract. And we must advocate, and preach, and teach, the same. But these practices must follow on from a lucid and thorough appropriation of Andrew’s important expositions and arguments. So I exhort you, as a matter of some urgency, to press into that task immediately. At the end of that road a joyful gospel awaits. Douglas Campbell Duke Divinity School

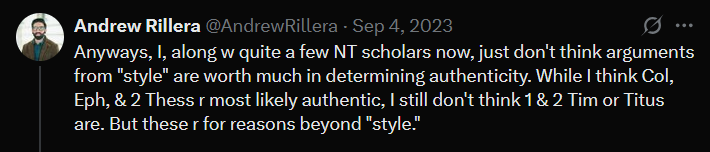

I think @atpollard and @Joe @TomL @TibiasDad will like this new book

This could very well be the best and most influential book written on Jesus death and its biblical meaning.

Andrew will summarize the key discoveries of this trajectory concerning the logic of OT sacrifice in what follows—and they are fascinating—so I do not need to do so here. The key point for us to grasp in this preliminary discussion is that this careful, historical work by Milgrom, along with those who argue like him, exposes the fact that the set of equations at the heart of the PSA model is, quite simply, untrue. The practice and logic of OT sacrifice has nothing to do with substitution, retribution, or punishment (i.e., negative retribution). Neither is it supplying a universal account of justice. The mechanism, logic, and concerns of OT sacrifice are completely different. As Andrew goes on to show, a number of significant reinterpretative tasks are set in motion by this realization, although I will mention just the key moves here since it will be better just to read what he says: 1.Where sacrifice is used in the NT, we now need to reorient our interpretations. What is going on in these texts is not PSA. A different logic is in play. Needless to say, the meaning of a lot of key texts utilizing sacrificial imagery shifts subtly but significantly—for example, the meaning of Romans 3:25. Andrew traces the most important such shifts in what follows. 2.Sacrifice disappears from many texts and arguments where previously we thought it was present. Simply because a passage discusses “atonement,” or even “salvation,” we no longer need to assume that the underlying logic and metaphorical register is actually “sacrifice.”

Many NT texts are consequently set free to make their own, more individuated contributions to our understanding of God’s saving activity through Christ. They can find different metaphorical fields and intertexts to be illuminated by. The discussion of soteriology, as Andrew shows, is diversified, complexified, and thereby enriched. 3.Financial metaphors and analogies are also caught up in this reevaluation. Simply because a text analogizes God’s work in Christ in terms of money no longer entails that God is enacting an event constrained by the parameters of negative retribution. God is not always exacting the payment of a debt from sinners meted out with pain. Something very different might be going on. Money and the financial system are, after all, very complicated metaphorical fields. They can speak much more clearly now of God’s gracious benefaction.6 The final critical result of all this reevaluation is, of course, that the account of the atonement in terms of PSA is damaged beyond all hope of redemption.

Its account of sacrifice is incorrect; its reach, presupposing sacrifice, is false; and its account of financial metaphors is false as well. At bottom, it has lost its biblical base almost entirely. (Andrew does not address appeals by PSA to non-sacrificial registers, but these will be limited and desperate.) It remains only then to press this good news through for all the rest of our thinking. We must press, that is, more deeply into a God of love, not retribution; into a God who eschews violence, rather than practicing it proportionately; and into a gospel rooted in divine benevolence and covenant, not in retribution and contract. And we must advocate, and preach, and teach, the same. But these practices must follow on from a lucid and thorough appropriation of Andrew’s important expositions and arguments. So I exhort you, as a matter of some urgency, to press into that task immediately. At the end of that road a joyful gospel awaits. Douglas Campbell Duke Divinity School

I think @atpollard and @Joe @TomL @TibiasDad will like this new book